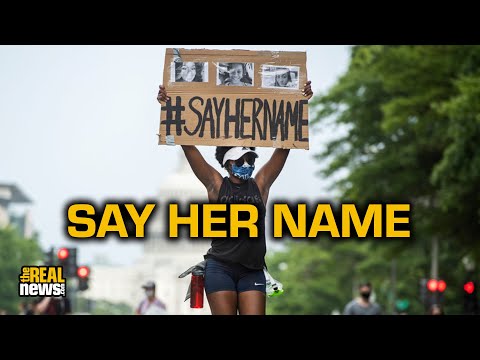

Historically, Black women like Fannie Lou Hamer, Atatiana Jefferson, Breonna Taylor, Korryn Gaines, and Eleanor Bumpers, who were killed or brutalized by police officers, receive less community outrage and media coverage than their male counterparts.

Story Transcript

This is a rush transcript and may contain errors. It will be updated.

Eddie Conway: Welcome to The Real News. I’m Eddie Conway, your host coming to you from Baltimore. We have been witnessing worldwide protests, strikes, demonstrations, destruction of monuments. When you look in the crowds you see men, women, children, white, black, brown, yellow, red, etc. And you hear more often than not a lot of names being shouted, or posters being bannered with Eric Garner’s name. Trayvon Martin’s name, Tyrone West’s name, Mike Brown. And of course we know all of this started with the killing of George Floyd. But what’s missing in this whole scenario, and not getting a lot of publicity is the name of women. Now of course we are Breonna Taylor’s name, because that’s an incident that’s closely associated with this whole thing. And some of us are aware of Sandra Bland, some of us are aware of other names of other women.

But in looking back at our history, of course we could go back all the way to slavery, but in looking back in our history, we can see names like Fannie Lou Hamer’s, being beaten by police, that affected her for the rest of her life. We see a case that I looked at in particular, was a case in Tyler, Texas in which an 84 year old … 82 year old grandmother was sleeping in her bed, police mistaking her house for a place to raid raided her house, charged upstairs and shot her six times in her bed. And walked away from the whole thing. The Grand Jury in Tyler, Texas found that it was an accident, the black community was outraged, they decided to do jury nullification. They in turn decided that they wasn’t going to convict any black person that didn’t do harm to the black community. And that was in ’92.

So young women, as young as seven, has been murdered in their beds by police. And women as old as 92 has been murdered in their houses by police. And so I wonder why we don’t hear more voices in these protests about the women that has been murdered by police.

This is not a black male thing, this is a people of color thing at this present time. So joining me today to talk about this a little bit is Dominique Conway, who is also my wife, writer, activist, organizer, educator. Also joining me is Professor Talitha LeFlouria. Thanks for joining me, Dominique and Talitha.

Talitha LeFlour…: Thank you for having me.

Dominique Conwa…: Thank you for having me.

Eddie Conway: Okay, my first question goes to you, Talitha. Over the years it seems that the police have killed one black woman a month. On average, which means sometimes there was two and then sometimes there might have been a month and a week passed by. But, why don’t we hear black women’s name? Why is this disparity between what the protestors are shouting out and what’s really happening in our lives?

Talitha LeFlour…: Thank you, Eddie, that’s a … a wonderful question. And a question that I’ve thought a lot about. Because as we know, the silence is deafening, right? And the level of outrage that we see shown toward the killing of black men and boys is just not shown when it comes to black women and girls. And I thought really hard and very long about this, and I can’t say that I have the answer, but one thing that I will say is that I believe that the numbers game has something to do with this. The fact that black women are killed in seemingly negligible numbers when compared with black men. So those staggering statistics that you shared, if one black woman is killed a month, then that means probably 10 black men are killed a month, right?

And so unfortunately people minimize the murder of black women and girls, because their numbers don’t compare with black men. But when you compare those numbers with the white women who are not being killed by the police, then that changes things. That helps us to see this in a different light, right? And so I’m not one who supports of promotes comparative suffering, and I believe that we need to move away from this narrative that somehow well, the numbers of black men that are being murdered are so much more, that we have to address that issue first, and then we can get to the black men. No, all black lives need to matter equally, including the lives of black women. And Kimberle Crenshaw recently said something that was so eloquent, and I want to share it because I think that it applies to what I’m saying now. She said that if your story doesn’t exist within a movement, that story isn’t entirely for you.

And so we have to lift up the stories of black women and girls, and we have to convey the message to the rest of the world that all black lives matter. Because if we don’t do it, if we show indifference toward the killing of black women and girls as a result of vigilante violence and state sanctioned anti-black violence, then if the black community doesn’t show outrage, then why should the rest of the world show outrage?

Eddie Conway: Okay, Dominique, the same question, why you think this silence around the death of black women at the hands of vigilantes, of police correctional officers, because a lot of black women are also killed in prisons. Dominique?

Dominique Conwa…: Yeah, I pretty much agree with what Talitha has said. I also do think it’s a difficult question because there are so many complexities. I think history, the devaluation of black women and the black female body, the black body in general, but particularly the black female body lends easily to that. So I think it’s very complex. I feel that white supremacy has set up a system in which there is a hierarchy. And even sometimes within struggles we reinforce that hierarchy, and I think we have to undo our thinking about how we view people within our own groups. And so I think that that’s part of the difficulty of really answering the question.

And I also don’t want to get into reinforcing a hierarchy and saying that well, it’s more important that we view the deaths of black women versus black men. No, we need to look at all of this because it’s not just black men, it’s not just black women, it’s our children, too. We’re pretty much all in the scopes of the rifle, and I think we need to view this as a war. And war takes everybody out.

Eddie Conway: Well Talitha, and I heard you say that it’s our story, we need to raise these stories up. What’s the role of black men in this, and what’s the role of black women? Because I see black women out there on the line also, talking about Trayvon Martin, and supporting protests around Eric Garner. And most of the time, and to be quite honest, most of the movements that I have witnessed throughout history and studied throughout history are actually led by women, and they are actually supported and pushed forward by women. And women has, from the time we got on the boats apparently, has been protesting, fighting, pushing, and in fact keeping us alive to fight the next day. But whose responsibility for bringing our story, the story of black women’s deaths also, whose responsibility is that?

Talitha LeFlour…: In response to your question, Eddie, about whose responsibility is, I think that it’s our collective responsibility to lift up the stories of black women and girls who have been killed by the police, or who have died at the hands of vigilantes. As Dominique said, white supremacist violence is indiscriminate. And so … but one of the things that I want to say is that as you mentioned black women have been doing a lot of this work. Black women have essentially been carrying the labor, they’re the ones who are showing up at the protests and who are committed to the defense of black women.

So when black men show up, even though unfortunately black men haven’t shown up at the same level that black women have, when black men show up for black women in these spaces and for black girls, what it says is that our lives are worthy of protection. That our lives are worthy of saving. As Dominique mentioned before, historically black women have not been afforded the same protections as white women.

Black women and girls, their lives haven’t been seen as worthy of the same protection. The dehumanization that slavery … the types of dehumanization that black women and girls and black people experienced during slavery, I think is part of the reason why we see this complete disregard for black life, and it’s part of the reason why black people can be killed with impunity. It’s because slavery set that precedent that our lives did not matter.

And so when a black woman is killed, or harmed, or injured, or when a black man is killed, or harmed, or injured, we’re all hurt.

Eddie Conway: Okay, Dominique, I’ve heard you say thousands of times that black men has a certain responsibility to speak up to other black men around this issue. Talk a little bit about that protest of Black Lives Matter activist, a young lady that reported a rape and after a rally she disappeared. Could you talk a little bit about the safe space, or the lack of safe space, and what’s the role of men in all of this?

Dominique Conwa…: Yeah, I feel like I don’t know enough about her particular situation to really speak to it. I’ve gleaned a few bits of information. So I don’t want to like go into that because I don’t … I just don’t feel comfortable speaking about her situation not knowing enough about it.

But I think in general … I mean, as a black woman it’s very difficult to feel safe in the belly of the beast. History has told me enough to know that I’m not safe, my children are not safe. When I have grandchildren, they will probably be … not be safe until this whole paradigm here is changed. But I do feel that it’s not just necessary for men to kind of take responsibility and acknowledge the deaths of these women as well, I feel like men need to be conscious of how they take up space when it comes to speaking to these issues a lot of times. My experience here in Baltimore and what I saw in 2015 was men taking up a lot of the talking space. But out on the streets I saw mothers, I saw grandmothers, I saw little girls. But when you looked at the interviews, what was reflected back very often were men who were not necessarily doing the organizing. And so I feel like brothers need to be conscious about taking up that space. Just like we tell white folks they need to be conscious about taking up our space, we need to look at who’s really being afforded ample room within our spaces.

Eddie Conway: Okay, and I [inaudible 00:14:06] one of the questions I was going to ask, and I realize that it’s probably not necessarily a valid question, considering that a lot of these cases that I’ve looked at of black women being killed, has happened in the spaces in their houses. They’ve been in their bedrooms, they’ve been in their living rooms, they’ve been away from videos and so on. So the video footage is not there, but I’m wondering about the 17 year old young lady that videoed George Floyd’s case, now I understand she’s receiving death threats, and she’s got to be hidden and protected. What should we be doing about stuff like that? Talitha, do you have any opinion on that?

Talitha LeFlour…: Wow, that’s a tough question to answer. I believe that we all have to obviously rally behind her, and support her, and support anybody who is a victim of white racial terror, even if it doesn’t result in death. Our community is being tremendously impacted, our public health … I mean, excuse me, our mental health is being affected. Racism is a public health issue. It’s a public health crisis. And so we as a community need to get around her and support her and lift her up, but we also need to hold the people who like, for example, people who provide mental health services, and social services, hold our local governments, our state governments, and any entity that could provide these kinds of resources in lieu of hiring additional police officers.

Part of the defunding of the police could involve channeling more resources into public health. Yeah, public health and mental health services for people in our community, including that young woman who I understand now is extremely agoraphobic and can’t even leave her house at this point because she’s afraid that she’s going to lose her life or that she’s going to be bullied or terrorized. People kill themselves when they are harassed and when they are terrorized in this way. So I just pray for her mental health and that she’ll be able to get the kind of healing and the attention that she deserves on an individual level, but we as a community need to also champion around her and other people who are brave enough to film these murders, and who are brave enough to speak out against these atrocities.

I think about Ida B. Wells. That young woman is the Ida B. Wells of our generation. She documented that horror, she documented that lynching, right? And so we have to get behind our brothers and sisters who are willing to document and put everything on the line, including their lives and their safety on the line to document these lynchings.

Eddie Conway: Dominique, and I guess this is like the final question, I would like for you to give us an idea of what should happen. I mean, we talk about defunding the police, some people talk about disbanding the police. Is that the real problem, or is the problem deeper than that, or what you think should happen to kind of like … the outcome of all this worldwide protests?

Dominique Conwa…: One, I do feel that it’s necessary to abolish police forces, but also I see the police as simply being the armed wing of a government that is at war with us and has been at best indifferent to our suffering, but a lot worse than indifferent. When you consider black Wall Street, and consider what happened in Tulsa, when you consider the attacks upon people of African descent, our communities as well as what is done to indigenous communities in this land. So I think yeah, it’s very necessary to abolish the police, but I think we also need to begin to determine … we need to determine our own destinies, and I hope that doesn’t sound too cliché at this point, but it’s true. And part of that is determining who’s going to really protect the communities. I feel like if we were in that kind of position, there wouldn’t be no question about protection for this young woman. As you all were talking about that situation I’m thinking we need a Deacons for Defense, we need some folks that’s going to stand outside that house armed and assuring her safety. Or whatever she feels would assure her safety, because that might not be it for her.

And so it is a matter of giving voice to everybody in the community to determine what their destiny is going to be, and what makes them feel comfortable. So I think that it’s very hard for me to say what needs to come out of this, because so much needs to come out of this, it’s been 500 years, okay? I think we have enough time for me to even go through the long list of things. But I think more important is that this is a young person’s game at this point. It’s their future, they need to be able to determine how they’re going to live that future, how they’re going into that future, and if there even is going to be a future.

Eddie Conway: Okay, Talitha, you get the final word. Do you have any final comment to share with our audience?

Talitha LeFlour…: So I just want to first of all thank you, Dominique, for your final word, and I agree with you wholeheartedly. I want to say that it is critical and it is paramount that we say the names of black women and girls. That we do not perpetuate or continue to perpetuate the invisibility that black women and girls face when it comes to these issues around police violence, and police brutality, and police terror. Black women and girls should not be a footnote, they should be at the center of these stories, at the center of our public discourse around police violence and anti-black violence. And it’s our responsibility to make sure that all black lives matter.

So whenever we can, we need to lift up the voices and the stories of black women, and join activists, local activists, nationally recognized activists who have really large platforms to speak out on these issues, including the African American Policy Forum. I would encourage you to contribute to and to support the Say Her Name movement. And to plug into the work that Kimberle Crenshaw and the African American Policy Forum and people who are committed to this work, and amplifying these stories all over the country are doing. And so that would be my final word.

Eddie Conway: All right, thank you. There’s a rally today, in fact, to support Say Her Name. So thank you for joining me Talitha and Dominique.

Talitha LeFlour…: Thank you.

Dominique Conwa…: Thank you.

Eddie Conway: Okay, and thank you for joining this episode of The Real News.

Studio: Cameron Granadino

Production: Cameron Granadino, Ericka Blount Danois