As the climate justice movement prepares for an historic convergence in NYC, political economist Patrick Bond warns that the “big tent approach” of the People’s Climate March might backfire

Story Transcript

SHARMINI PERIES, EXEC. PRODUCER, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Sharmini Peries, coming to you from Baltimore. This is another edition of The Patrick Bond Report.

The official UN climate summit of world leaders are to gather in New York next week, focusing our attention on the grave climate crisis before us. To put pressure on the world leaders, a people’s march is also being organized by the environmental movement on 21 September, also in New York.

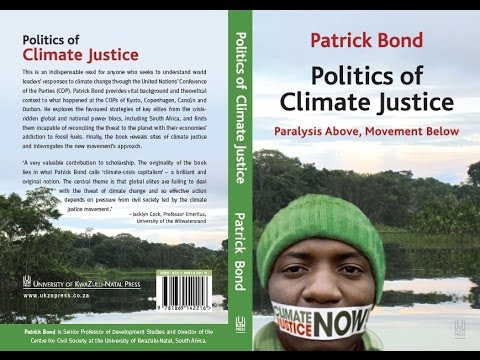

Now here to talk about the summit and the People’s March is Patrick Bond. Patrick Bond is the director of the Center for Civil Society and professor at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, and he’s the author of Politics of Climate Justice: Paralysis Above, Movement Below.

PATRICK BOND, DIRECTOR, CENTRE FOR CIVIL SOCIETY: Thanks, Sharmini. Great to be back with you and the viewers.

PERIES: So, Patrick, you are planning on being in New York for this great world leaders summit, as well as a global convergence of various social movements coming together to protest what’s happening to our climate. What is your initial take on what’s going to be happening?

BOND: Well, it’s an extraordinary opportunity to see how the climate justice movement is reconverging. It’s a time when the heads of state will be meeting, on Tuesday the 23rd, with no expectations of any major breakthroughs, probably more gimmicks, a series of announcements by heads of state that really, probably, will continue the paralysis and maintain the fiction that there will be some technical fixes, and also carbon trading, market-based strategies.

In contrast, what I’m most enthusiastic about, Sharmini, is how well the climate justice movement, especially Climate Justice Alliance, with many groups from around grassroots and sites of struggles [incompr.] environmental justice that involve people of color in the United States, And they’re in Alliance with many groups across the world. And the Global South will have a fair representation of activists, the Pan African Climate Justice Alliance from this continent, for example.

And between the 18th, when Naomi Klein launches her new book, which is going to be quite a blockbuster, by injecting the word capitalism very firmly into this debate, can climate change be a source of inspiration to change capitalism, the book called This Changes Everything, launch on Thursday, right through to the subsequent Thursday. Lots of talking, strategizing. And then a big march, probably a couple of hundred thousand people in New York City. And then direct action the next day on Wall Street, protests throughout that week. And I think those are the kinds of opportunities, when the climate justice movement has been on its back foot, really, since Copenhagen–. Here in Durban in 2011 you’ll recall we hosted the alternative climate summit, and the CJ movement really haven’t recovered from a kind of shock at trying to make change at the global scale. And I think in the meantime we’ve seen a great deal more happening at the local scale, and that’s what’s going to be brought together in an attempt to connect many of the dots to find common themes.

PERIES: One of the things that is happening is, in terms of the broad climate march that’s going to be happening in New York, a number of corporations have actually signed on to the march and will be marching with everyone else, group called Climate Group, which is a constellation of corporations, some of them actually contributing to fossil fuel emissions and pollution of our oceans. What do you think of that? And what is the role they’re playing in the broader gathering?

BOND: Well, I think that will be considered a big mistake. Those groups include Chevron and Exxon, that world’s number one and two historic emitters of CO2. And it reflects a sort of big-tent approach that some of the organizers have thought advisable. Now, I can’t second-guess them, because it’s their terrain, being it in New York, but, for example, to see pictures of subway signs advertising that hipsters and bankers are in the same boat, the boat crossed out with march amidst a sort of background of a sea, suggesting that the bankers really have some role in solving this problem. Well, they’ve been trying. Since 1997, the Kyoto Protocol, it’s really been a bankers strategy of allowing the big corporations to continue emitting, especially in Europe, the pilot for carbon trading, and then letting the bankers try and sort out how a system can be devised that would most efficiently allocate the right to pollute by basically privatizing the air and putting it up into the financial markets. Well, needless to say, like so many of the financial market gimmicks we’ve seen in the past 15, 20 years, this one also a dramatic failure, with the European pilot crashing.

What I’m worried about is the strength of neoliberalism, that free-market ideology, the power of bankers and their mentality, not just allow them into the march. But probably on Tuesday we’ll be hearing, for example, that not only California, but China, maybe some of the other BRICS countries, South Africa, starting carbon trading on their own and eventually trying to link up a carbon trading network–way too little, way too late, when it’s absolutely clear that we need explicit caps and bans. And, indeed, we had word this last week that the Montreal Protocol–that was the agreement in the United Nations in 1987 that banned chlorofluorocarbons and stopped the ozone hole from growing–has been a success. And that’s the kind of wide and broad and very firm state action that there’s no question we’re going to have to ultimately revert to, not to privatizing and gimmickry like carbon trading. Therefore I would worry that the big-tent approach, bringing everybody who says they care about climate in even if it’s to make a few bucks, like the bankers, is the wrong approach for that Sunday march, and also the failure to have a real set of demands and a rally and to have the march confront power. It’s marching away from the United Nations. These are the kinds of questions I think people will be asking. And as a result, those with a more strong and activist orientation taking heart that on Monday on Wall Street, activists have put together, with the Occupy movement, an idea called flood Wall Street, harking back to Sandy, that hurricane in November 2012 that flooded Wall Street and began to wake up this very backward little island from its sleepy days that maybe climate’s not a problem. Well, they realized losing about $60 billion in infrastructure and damage across the New York-New Jersey-Connecticut coastline and that little island nearly sinking, that even Wall Street is quite vulnerable to climate change.

PERIES: Patrick, one of the criticisms of the IPCC and all the efforts of the UN is that they actually in the last 25 years has not been able to come up with a treaty, or any agreement, for that matter, on climate change. Why is this summit happening? And is there any hope that anything more concrete will come out of such a summit focused on climate change?

BOND: Yes. The IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, regularly issues reports every five years, major reports, and they have been behind the curve and very conservative. The situation’s worsening faster than the IPCC’s always anticipated. They did win the Nobel prize. And these reports do raise consciousness. And they compelled Ban Ki-moon, the UN general secretary, to at least call, a day ahead of its usual heads-of-state summit, a special one-day discussion.

Now, the question is: can the balance of forces shift dramatically before next Tuesday and then before the next COPs? One is the Conference of the Parties 20 in Lima, Peru, in November. And then the following year in Paris is meant to be the very big COP 2015, where perhaps several hundred thousand people will be out protesting. And, now, those are the chances to really do something at the global scale. But as you said, we haven’t had any global treaty, no progress toward it worth describing, the Copenhagen Accord the last really big chance, and that ended up being very destructive, because Barack Obama got together with the South African, Brazilian, Indian, and Chinese leaders to cut a side deal, the Copenhagen Accord, which was entirely voluntary and very weak pledges. Four degrees is pretty much guaranteed with that Copenhagen Accord. And as a result, you can really feel that this balance of forces in which these corporations have much, much more power than, say, back in 1987 when the Montreal Protocol banned the CFCs. And these corporations in the fossil fuel sector, as well as their facilitators, the bankers, the financiers of fossil fuels, as well as the transporters–and I feel that in this current period, the divestment movement can target the fossil fuel companies, as well now, for example, with Keystone Pipeline, as the companies running the oil on trains and in the pipelines, these are the kinds of new innovations that here in South Durban, where we have a huge petrochemical complex, the biggest in Africa, and a proposed $25 billion expansion of our shipping industry right here in this port, the largest in Africa–. And those are the contestations that we’re going to see and we already have in the last few months, quite angry communities up in arms, with environmentalists saying, really we’ve got to factor in climate and not go ahead with this port petrochemical expansion.

And you know, Sharmini, all over the world it’s that microscale of protests right at the fence line and the coal face, if you will, of so many of these fossil fuel projects that I feel we can increasingly rely on, since [the global (?)] is not really going to be changed dramatically enough in the next period to invest any hope in a global deal. We really have to be much more local, but also more militant and much more connected to each other. That’s the challenge ahead for climate-justice activists.

PERIES: And finally, Patrick, the absence of both China and India at this summit has been talked about quite a bit, but what are the reasons for them not attending the conference?

BOND: Well, the ultimate reason is that these will be the countries that are on the growth trajectory of fossil fuel consumption, though, to be fair, China has registered last week a 5 percent decline in coal consumption, and for South Africa, which exports coal, that’s something that we hope will worry the big coal companies.

However, China and India are as the workshops of the world, more or less now, exporting and therefore, in a sense, the victims of the outsourcing. And because the outsourcing of carbon still hasn’t been properly factored into global discussions–in other words, you in the United States are consuming so many products that used to be made in the U.S. but now are made in China, and hence the carbon emissions associated with those products really should be on the United States’ account. And for the climate debt, the so-called loss and damage to be paid, that’s going to be an important factor.

I feel the Chinese, the Indians, especially with that new, very right wing government in Delhi, and also the Russians, who dropped out of the Kyoto Protocol, even the Brazilians, allegedly the more green force within the BRICS, and, of course, the South Africans [going ahead (?)] with big coal-fired power plants, fracking, and a variety of other big fossil-centric projects, really suggests that these BRICS, the Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa emerging market network actually amplify these problems at the global scale. They’re not really an alternative or a solution to the world’s problems; I fear they actually will make these worse.

PERIES: Patrick, thank you so much for joining us.

BOND: Thank you very much, Sharmini. Good to be with you.

PERIES: And thank you for joining us on The Real News Network.

End

DISCLAIMER: Please note that transcripts for The Real News Network are typed from a recording of the program. TRNN cannot guarantee their complete accuracy.