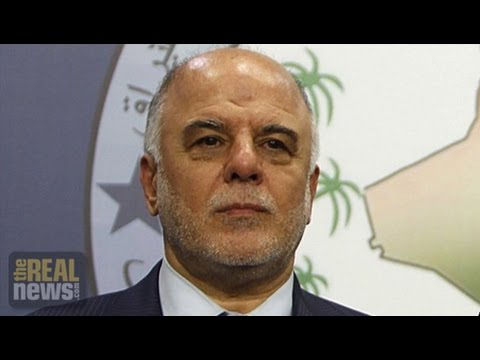

IPS’s Phyllis Bennis discusses the interests new Iraqi prime minister Haider al-Abadi represents and the main issues to pay attention to as his administration moves forward

Story Transcript

JESSICA DESVARIEUX, TRNN PRODUCER: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Jessica Desvarieux in Baltimore. And welcome to this edition of The Bennis Report.

Now joining us is Phyllis Bennis. Phyllis is a fellow and the director of the New Internationalism Project at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, D.C. She’s also the author of many books, including the book Ending the Iraq War: A Primer.

Thanks for being with us, Phyllis.

PHYLLIS BENNIS, FELLOW, INSTITUTE FOR POLICY STUDIES: Good to be with you, Jessica.

DESVARIEUX: So, Phyllis, Iraq has a new prime minister, Haider al-Abadi. Whose interests does this new prime minister represent, in your view?

BENNIS: We don’t know yet is the quick answer. He is from the same political party as his predecessor, Nouri al-Malki, who was responsible, with U.S. backing, for the vast majority of sectarianism that has been on the rise in Iraq for the last eight years or more. We’ve heard some interesting language from Mr. al-Abadi, saying that he intends to move towards a more inclusive government, something that’s obviously key to maintaining the unity of Iraq and, in the immediate, being able to win the battle against the extremists of ISIS, or the Islamic State. The reason that they’re winning so profoundly is because they have a lot of support from a lot of different sectors in the Sunni community.

Whether the election of a new prime minister who comes from the same political party but is a little bit different in orientation, whether that will be enough we don’t know yet. We haven’t heard yet what the plans are for al-Abadi and his new government. One of the real problems is that putting together a new government is no easy task. That’s going to take some time. Putting together a strategy for holding the country together, that’s going to take some time. And in the meantime, it’s not very likely that the support for ISIS will end in the immediate, until people see what the real intentions are and what the real capacity is of the new government.

DESVARIEUX: And, Phyllis, amidst all of this political shuffling, there’s the story of that Christian community in northern Iraq that was trapped on a mountain. And the media was originally reporting something like tens of thousands were there, but now the Pentagon is saying that it’s not as bad as they had feared and appears unnecessary that they will have to actually rescue this community. So what do you take out of this, this sort of–because we were hearing from war hawks calling for more boots on the ground and using this community as a reason for intervening.

BENNIS: Well, we were hearing a lot about this community. This is not a Christian community; this is the Yazidi community, which has roots in pre-Christian religions, in Christianity, in Zoroastrianism, as well as in Islam. And it’s one of the smaller minorities in Iraq that was very much threatened by ISIS. There’s no question about that. On the other hand, they were one of many non-Shia communities that faced sectarian discrimination in Iraq from their own government under al-Maliki.

Now, I think that the seriousness should not be underestimated. I think part of the reason that it’s not so bad now, as the Pentagon is saying, is that Kurdish fighters, Peshmerga fighters from inside Syria, have managed to open a safe corridor off the mountain, sort of from the back way, if you will, into Syria and looping around and then coming back over the border, back into Iraq to safety. They were saved, essentially, by Syrian Kurds allied with the Turkish organization the PKK, which is, of course, listed as a terrorist organization in the United States. It’s not surprising that the U.S. doesn’t want to acknowledge the key role of these Kurdish fighters, who they don’t like very much most of the time. But I think if they want to use as an excuse the fact that it’s no longer necessary to say that they’re going to pull back the further U.S. militarization that’s been underway, that would be a good thing. It’s not a true claim, but if that’s going to be their excuse, better that they make a false claim and act in the right direction than the reverse.

DESVARIEUX: Okay. I hear you on that point.

And, again, another interesting point is the U.S. and Iran actually kind of more or less being on the same page about this new prime minister coming to power. What does this mean for the relations between the two countries?

BENNIS: Well, this depends a lot on issues of political will. This is one of the more overt and more acknowledged examples of a number of instances in the last couple of years where you’ve had the US and Iran objectively on the same side, particularly in Iraq. Throughout the last years of the war, in the U.S. efforts to shore up this corrupt and sectarian government in Baghdad, the U.S.–our tax dollars have been paying for that government, paying for the parliament, paying for the military, which has been acting as, essentially, the biggest Shia militia in the country, as opposed to it really acting like a national army. But in that context, the U.S. and Iran were supporting the same guide. We were both supporting the government of Nouri al-Maliki. Now, it’s clear that al-Maliki saw himself and continues to see himself as much more accountable to Iran than to the United States, despite the fact that the U.S. is paying the bills, but this is one of those moments when the U.S. is already engaged in talks with Iran, the really important talks over the Iran nuclear crisis, the one example of a foreign-policy issue where President Obama has a chance–if they do it right, he’s got a chance to have a real victory come out of this. It would be his almost only foreign-policy victory. So I think they’re trying very hard not to scuttle those talks. Whether those talks could be expanded, for instance, beyond the immediacy of the nuclear crisis to a broader, new relationship, a new beginning of the relationship between the U.S. and Iran, starting with the unity of interests in stability in Iraq, a new government in Iraq, etc., that could bode well for the possibility of what has long been known as a grand bargain between the U.S. and Iran.

DESVARIEUX: And, Phyllis, for our viewers out there who are following this story closely, what are some things that you would recommend that they pay attention to?

BENNIS: I think we have to pay attention to what kind of support the new government has in the parliament. Who are the people that the new prime minister appoints to key positions, such as in the Ministry of Interior, Defense Ministry, etc.? Does he pull in non-Shia members of parliament to play those very important roles, giving the Sunni, the Christians, and others a real stake in the governing of the country? Those would be important signs that his intentions are really to open up the government and move away from the kind of sectarianism. So that’s one aspect.

Another will be: what’s the position that we’re going to be hearing from the Kurdish leadership? Are they going to use the moment that they now have been presented with from the United States, where the U.S. is acting essentially–despite their language to the contrary, they’re acting as the air force of Kurdistan, the air force of Iraqi Kurdistan. Are they going to use that to make greater claims for independence, something that has been a long-standing Kurdish goal but is quite contested among Kurds and others, whether what’s really wanted is greater levels of autonomy. Or is it really fully dependence that would lead to the splintering of Iraq?

And in that context, the third thing to keep an eye on is this question of oil. One of the big issues, part of the reason that the U.S. is so worried about the possibility of ISIS approaching Erbil when they weren’t so worried when they were seemingly approaching Baghdad is because of the question of oil in the Kurdish region of the North. There is, obviously, a lot of oil in the Kurdish region itself. The Kurdish regional government has been signing contracts with oil companies all around the world without allowing the government in Baghdad to be engaged in that the way it’s supposed to be legally. And the Kurdish fighters, the Peshmerga, have used the opportunity of the recent crisis and the fighting against ISIS to expand their own control. They’ve taken over, for example, the city of Kirkuk, which has been contested for many years, whether it belongs in the Kurdish north region or in the broader central region of Iraq. That’s important not only because it’s a very mixed city–not everyone there is a Kurd, not everyone there wants to be part of the Kurdish region–but also, crucially, there’s massive oil access in and around Kirkuk. So whoever controls Kirkuk controls a great deal more oil. That’s obviously something of great concern to the United States.

DESVARIEUX: Alright. Phyllis Bennis, many things for us to keep in mind. Thank you so much for being with us.

BENNIS: Thank you. It’s been a pleasure.

DESVARIEUX: And thank you for joining us on The Real News Network.

End

DISCLAIMER: Please note that transcripts for The Real News Network are typed from a recording of the program. TRNN cannot guarantee their complete accuracy.