Maurice Carney: A U.S.-based unit has been selected as the Army’s first “regionally aligned†brigade, and by next year its soldiers could begin conducting operations in Africa.

Story Transcript

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Washington.

On May 16, General Ray Odierno, the Army chief of staff, announced that AFRICOM, the American military mission in AFRICOM, would expand its activities, sending soldiers throughout the continent in a new plan of training, and it would involve a new combat detachment. Now—combat division, I should say.

Now joining us to talk about this is Maurice Carney. He’s the executive director and cofounder of Friends of the Congo, based in Washington, D.C. Thanks for joining us, Maurice.

MAURICE CARNEY, EXEC. DIRECTOR, FRIENDS OF THE CONGO: It’s my pleasure being here with you.

JAY: So what do we know so far about this mission, and what do you make of it?

CARNEY: Well, the mission itself represents an escalation of the militarization of the African continent, and really it’s a logical extension of what has transpired since the establishment of the Africa Command in 2008 under President Bush and initiated by Donald Rumsfeld, which has, unfortunately, been carried on by the Obama administration. So the announcement of brigades [incompr.] continent rotation is not much of a surprise at all.

I must add quickly that although the United States has continued to push AFRICOM, it has been roundly rejected by African leaders. An initial aim of AFRICOM was to establish a based presence on the African continent. And because of the, you know, vicious or, you know, intense pushback on the part of African leaders, President Bush had to backtrack on that aim. But nonetheless we still see the push for AFRICOM to have a large footprint on the African continent.

JAY: And where is AFRICOM operating now? Where is its main base of activities, and where else is operating?

CARNEY: Its headquarters right now is in Stuttgart, Germany. However, it operates throughout the continent. When AFRICOM was first launched, headed up by Kip Ward, an African-American, we were told that AFRICOM would be primarily concerned with humanitarian issues—digging wells and training and providing support in disaster areas. But we quickly saw with the NATO onslaught in Libya that that was led by the Africa Command. And so we see that the guise of the U.S. militarization of the African continent under humanitarianism is nothing but that, a [‘ʃɪbÉ™lɪf], let’s say.

What we are clear about and understand: that the driving push, you know, for AFRICOM is for the United States to protect its strategic and economic interests on the African continent, especially in the face of competition for access to natural resources that United States in particular and the West in general is getting from China’s expansion on the African continent and the economic ties that the Chinese are establishing.

JAY: Now, the press reports of AFRICOM and the reason suggested is this has to do with al-Qaeda type organizations operating in various countries. I mean, how real is that issue?

CARNEY: There are terrorist groups operating, you know, in Somalia and the Maghreb, Sahara, Northwest Africa. But I think it’s overblown, because if we look at where AFRICOM is and where it’s operating, it’s not solely in areas where we see some presence of terrorist groups. I’ll give you an example. In the Central African region, for example, there are no terrorist groups in—that we’re aware of, anyways—in Rwanda, and they receive large shipments of equipment, they get training, intelligence, and money from the United States. So although terrorism is a casus belli for the United States, we see that the larger issue is the protection of their strategic interests and their economic interests on the continent.

JAY: Now, you were saying there’s been a pushback by many African countries on the role of AFRICOM, but on the other hand, many African countries are kind of rather friendly to the United States, and there’s been a lot of popular resistance to them, if I understand correctly, in terms of Arab Spring—there’s been somewhat of an African Spring, quite violently repressed by many regimes. Is there any evidence that AFRICOM is supporting, training, or connected to any of the more repressive measures by various governments?

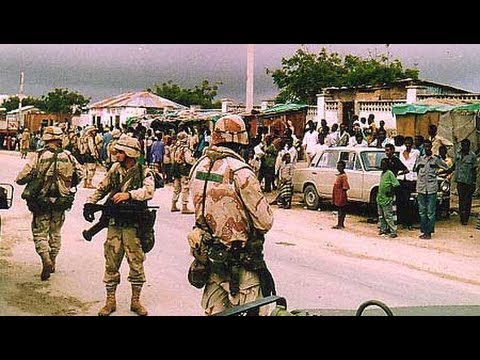

CARNEY: Certainly, and their relationship with these repressive regimes predate AFRICOM. You really have to go back to the early 1990s when the U.S. had its military presence in Somalia and we had the Black Hawk case that everybody remembers. Since that time, the United States had vowed not to have its troops be subjected to that kind of humiliation. And in the Clinton administration what was developed was a policy that was dubbed the Renaissance leaders of Africa, where the United States identified several leaders as the future leaders, the so-called Renaissance leaders of Africa. They included figures such as Paul Kagame of Rwanda, Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, Meles Zenawi of Ethiopia, who was just invited here to the United States for the G-8 meetings at Camp David. So those are some of the figures.

And one—a couple of the things that those individuals that I just named have in common: one is they’ve invaded another African country; and two, they have the blood of millions of Africans on their hands, whether it’s through the invasions or through the repressive measures that they impose on their own people. So we find the United States, dating back to the Clinton Administration, through the Bush administration, and now the Obama administration, in bed with some of the most repressive, vicious dictators that we see on the African continent, who have been in power for decades, as in the case of Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, who’s been in power since 1986.

JAY: And AFRICOM recently sent 100 troops or so to Uganda, did they not, in other words, winding up supporting the Ugandan military?

CARNEY: Oh, absolutely. Not only did they send 100 troops, but prior to sending troops, they sent $45 million of aid and equipment [incompr.] drones to Uganda. And Uganda has—as I’ve shared with you, it’s been one of the most repressive regimes on the continent, invaded the Congo twice with its partner Rwanda, both in 1996 and in 1998, and has been sanctioned by the International Court of Justice. The Congo brought Uganda to the court for Uganda’s invasion and looting of Congo. International Court of Justice said the Congo’s entitled to $10 billion in reparations.

So with the U.S. increasing its aid to Uganda, sending advisers, and, unfortunately, getting young people—where we see so-called humanitarian institutions calling for U.S. military engagement in Uganda and the South African region under the guise of humanitarianism, in pursuit of a war criminal named Joseph Kony, we think that’s one of the most unfortunate occurrences that we’ve seen so far this year and in recent times, where basically you have 13-year-olds clamoring for the U.S. military to have a presence on the African continent, particularly in support of a known dictator, an authoritarian figure. So that raises tremendous concerns for us, because it provides yet another cover for the United States to increase its militarization of the African continent, and in this case Central and East Africa.

JAY: Right. Now, you were talking about China and the contention with China over the resources of Africa, but China doesn’t have any troops to speak of, do they, in Africa? So what good does AFRICOM do the United States in terms of this competition with China?

CARNEY: Well, I mean, China’s presence is primarily represented by its economic heft, that is to say, its ability to invest in large projects [incompr.] that the United States and European nations just cannot compete. Take the Congo for example. China looked to invest $9 billion in the Congo in a mineral-for-infrastructure swap, where Chinese [provide] roads and rail and hospitals and schools in exchange for Congo’s copper and cobalt.

And in that scenario we saw the West pull out the arsenals at its disposal to challenge China. Because it cannot compete on an economic level, they use their multilateral institutions, and in the case of the Congo they use the International Monetary Fund. And the International Monetary Fund, which funds the Congolese government, called for the deal to be renegotiated. In other instances, they may use the military, because that’s where they can compete, where the U.S. aligns itself with these strongmen that we see in Rwanda and Uganda and Ethiopia and elsewhere. And as a result of this military alignment, the United States is able to secure access to natural resources, whether it’s, you know, strategic minerals or oil.

JAY: Right. But China’s had no problem working and investing in countries that have repressive dictatorships. They don’t seem to have any issues with supporting dictators themselves, do they?

CARNEY: Well, they have no problems in working in repressive environments. You’re correct on that regard. And this is—that’s an excellent point that you bring up, where—this is where African civil society and social justice movements come into play, because whether you’re talking about China or you’re talking about the United States or European nations, the destiny of Africans cannot be left in the hands of foreign powers. It’s the African people that are best placed to protect the interests of Africans.

One positive sign in terms of [relations] with [incompr.] Africans with China is that China will just as well operate in an environment where there is a dictatorship, but also an environment where you have a Democratic-elected government, as long as their economic interests are protected. And we haven’t seen any indication where the Chinese would look to go in and overturn a government or back a coup in order to protect its economic interests, which just to the contrary we see, whether it’s with the United States, the European nations. They will certainly go in to try and change the political equation so that it works in their benefit.

JAY: Alright. Thanks very much for joining us, Maurice.

CARNEY: Thank you.

JAY: And thank you for joining us on The Real News Network.

End

DISCLAIMER: Please note that transcripts for The Real News Network are typed from a recording of the program. TRNN cannot guarantee their complete accuracy.