Imagine if the climate crisis was a musical composition oscillating between musical highs and lows, between hope and despair. The ClimateMusic Project, in collaboration with Richard Festinger, a music composer and educator, has written the “science-guided” musical composition “Icarus in Flight” using environmental datasets spanning two centuries.

The composition was recently performed by San Francisco’s Telegraph Quartet to celebrate Earth Day on April 22 in collaboration with the National Academy of Sciences (NAS).

“Icarus in Flight” premiered in 2018 as the second musical composition commissioned by the ClimateMusic Project, a small San Francisco-based organization harnessing the power of music to motivate public action. The datasets used in this musical piece correspond to three main human drivers of climate change: fossil fuel use, population growth, and land use change between 1880—2080.

The data used in the composition was sourced from projections developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—the international organization tasked with coordinating global climate research and actions.

Richard Festinger, the composer of “Icarus,” says music is a better way to get people to act on the urgency of climate change compared to scientific lectures and graphs, or data. Talking to TRNN, Festinger said “through ‘Icarus in Flight,’ I wanted to emotionally convey the problems that climate change poses and motivate people to take action.”

To Laurie Goldman, director of public engagement for the ClimateMusic Project, the idea behind these compositions is to show two likely scenarios: the business-as-usual approach where we don’t take enough action and the mitigation scenario where we take appropriate action. “Music is definitely the right tool because everybody listens to some kind of music no matter where they are,” she added.

From lifeless data to living piece of music

“Icarus in Flight” is a nearly 30-minute long performance piece and is divided into three equal parts, each representing a range of years: 1880 to 1945, 1945 to roughly the present day, and present day to 2080. Festinger says the composition is the result of a collaboration between himself and a small team of scientists which turned lifeless data into a living, breathing piece of music.

“When we started discussing my piece with the ClimateMusic Project and their science team, we made the decision to use data reflecting human drivers of climate change.” Therefore, datasets corresponding to population growth, carbon emissions, and increasing land use projected over 200 years became the basis for the composition.

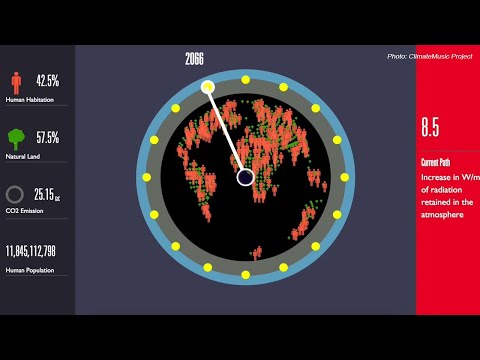

The real question was how to use these datasets to organize certain aspects of the music, Festinger said. Putting it simply, population growth is notated by the density of music, while progression of musical notes from lower to higher frequencies signify the increase in carbon emissions. Finally, non-standard playing techniques which produce unusual musical tones represent the percentage of land adapted to human use. “Each year of historical time is represented by about eight seconds of musical time,” he added.

Emphasizing that the melodic content of “Icarus in Flight” was left entirely to his choosing, Festinger said it was a team decision how the beginning of the piece would depict the evolution of the IPCC data. For the third part of the piece representing the future projected out to 2080, “we made the decision that the music would alternate in a kind of best-case scenario and the worst-case scenario.” This alternation between the two possibilities gave the piece its musical progression between hope and despair, the hopeful and the damned.

Goldman told TRNN “the intention was to perform this piece for the audiences that enjoy chamber music. The idea is to create new insights for them so that they’re motivated to action. We also have action partners that will allow people who are motivated by these performances to have a pathway to action.”

Who is ‘Icarus in Flight’ meant for?

The technical details and musical prowess that went into composing the piece also prompt a critical question: Who is this music really meant for?

The complex science of data modeling and layers of musical instrumentation make it challenging for any non-expert to appreciate “Icarus” fully. Does this not make it music by the elite and for the elite—at the expense of the millions, mostly in the Global South, who are bearing the brunt of climate change in the form of deforestation, drought, water scarcity, and seasonal shifts with little hope in sight?

Addressing this point, Goldman said the ClimateMusic organization has reached thousands of people but the intention is to reach millions of people in order to scale up action and convince people that it’s a really important issue. “We have only scratched the surface. So, our next step is to create a tool to allow musicians from around the world to do climate music and engage their own community.” She added that in future the organization intends to expand into schools and museums to reach out to wider community with their message.

In his response, Festinger said the musical performance was accompanied by an explainer video illustrating the increase in carbon emissions, land usage, and population increase over time to make sure the audience understood the context. “Personally, I write the kind of music I write. I don’t really think so much about who I’m writing for as thinking about what I need to write as a composer. I like to think music is a universal language and anyone listening with open ears and an open mind might be able to tune in to the emotional qualities of the music and be able to follow the sense of catastrophic increase in different datasets.”

Jeremiah Shaw of the Telegraph Quartet drove a similar point, saying “there are so many languages in the world. You might not understand the language but you can appreciate it.”

The talented cellist said the manner in which a word is spoken or a piece of music performed can communicate with the audiences. “You can kind of feel the emotion behind it. If we can affect them, if we can make them smile or get a tear in their eye, those things you can’t really explain how that happened and that’s what we love about performing,” he added.