Duménil: Neoliberalism imposed a new discipline on worker, cutting the progress of purchasing power.

Story Transcript

INTERVIEW WITH GÉRARD DUMÉNIL (Part 1 of 2)

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Washington. And joining us again from Amherst, Massachusetts, from the PERI institute studio is Gerard Dumenil. He’s an economist at the University of Paris. He’s the author of an upcoming book, The Crisis of Neoliberalism, from Subprime Crash to the Great Contraction. Thanks for joining us again, Gérard.

GÉRARD DUMÉNIL, ECONOMIST, UNIVERSITY OF PARIS WEST: Thank you.

JAY: This word, “neoliberalism”, which is in the title of your book and used by many economists many times, often doesn’t get explained. So start from the beginning so we can get to the current crisis. What do you mean when you say you “neoliberalism”?

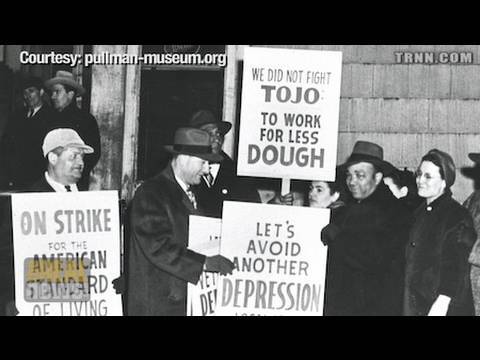

DUMÉNIL: When we speak of neoliberalism, we speak of contemporary capitalism. Neoliberalism, it’s a new stage of capitalism which began around 1980. It began in big countries like United Kingdom and the United States. Then it was implemented in Europe, and later in Japan, and later around the world in general. So this is a new phase of capitalism. The characteristic of this phase of capitalism is a specific violence. It’s a new phase of capitalism in which the objective, you know, was to restore and increase, and increase tremendously, the income of classes of people who are making—you know, the upper fraction, you know, of the population in terms of income. And in this sense neoliberalism was very successful. It was very successful to the present crisis, okay, which is the crisis of neoliberalism. This was done by imposing a new discipline to worker, cutting the progress of purchasing power. It was done through the neoliberal globalization, which means free trade, free movement of capital around the world. It was done by a new economic policies.

JAY: Why were they able to implement this at that time? I mean, one must assume that the upper echelons, the upper 5 percent or 1-2 percent, I mean, they always want to maximize how much they can make. So what was specific about that period?

DUMÉNIL: Because, you know, after the Great Depression, after World War II, during the first decades after the war, the political situation was completely different, you know? And in the world there was a very important movement of class struggle. There was a worker resistance, you know, not only in the United States but around the world in general. You know. So, actually, capitalist classes were forced to compromise, okay? But the point is that in the 1970s there was a big structural crisis in the world, in particular in those countries with cumulative inflation and so on, and there was a new phase of struggle, new phase of confrontation. And there was—so capitalism classes were moving forward, you know, and tried to implement this new social order which would be more favorable to their interests, okay? There was a very big resistance on the part of worker, with big strikes in England, big strike in the United States, you’ll remember. It was the period in England of Margaret Thatcher, period of Reagan, and so on. And, actually, this was a new piece of the class struggle, in which, you know, popular classes lost and capitalist classes and upper classes in general won. But they were able to impose this new social order.

JAY: Now, a lot of that had to do with the industrialization and the raising of skill sets in countries with much cheaper labor. Was that not a major factor in [inaudible]

DUMÉNIL: Yes. No, that is the reason why I mentioned—you know, among the methods of neoliberalism, I mentioned globalization, neoliberal globalization. Neoliberal globalization means opening, you know, frontieres [borders] to trade and to the movement of capital, which means a capability to invest anywhere in the world. So this is exactly what’s happening now. I mean, if you compare wages in country like China, or even worse if you compare wages in the US and wages in Vietnam, for example, in Vietnam a worker in a factory will make $50. A worker in Guatemala, woman working in what we call the maquiladoras, okay, in Guatemala, or, you know, [inaudible] Latin America will make, you know, $50 a month, alright? So, of course, you know, neoliberalism place all workers of the world in a situation of competition. And this had, of course, you know, an effect, very strong effect on their capability to control wages, purchasing power, and any kind of social protection in the sense of health, you know, unemployment benefits, or anything. So this was one aspect of neoliberalism. But neoliberalism is not only neoliberal globalization; it’s also, for example, a new way of managing corporation. Now, in neoliberalism, corporation are managed with only one objective, in particular the United States, which is maximizing the value of their share of the stock market. This is called, you know, create value for stockholders. And if you look at the data, you’ll find that they were very successful, because indeed, to the present crisis, the stock market indices increased tremendously, distribution of dividend to shareholders, you know, increased tremendously.

JAY: This has a lot to do with creating various bubbles.

DUMÉNIL: Yes, of course. You know, neoliberalism—one aspect of neoliberalism that we have not mentioned which is crucial in the present crisis is what we call financialization, and this means, you know, developing financial mechanisms, because they are making, of course, a lot of money on that. But the condition for that was deregulation, because the activity of the financial sector was limited by many regulations, often inherited from the Great Depression, okay? So, gradually they were eroding that. You know. But it’s a constant process, and to the present crisis it went growing. You know. And there is actually—you know, if you look, for example, the year 2000, you know, really marks a limit, you know. After 2000, all these mechanisms, like financial mechanism, you know, develop at an absolutely incredible speed. If you look at the data, you see after 2000 an incredible explosion of financial mechanisms. And this was one of the causes of the present crisis, for which now workers are paying, like in Greece.

JAY: Over this period you have a massive transfer of wealth from the majority people to this top two, three percentile.

DUMÉNIL: Oh, yes. Oh, yes. In income statement, you know, data these appear. And this is absolutely a tremendous mechanism. It’s called, you know, in the press a “growth of inequality”. But actually it’s a class phenomenon. And the answer to that by the right is, well, inequalities are growing, but everybody’s benefiting—which is total bullshit, if I can say.

JAY: Yes, you can.

DUMÉNIL: You know, in France we are gross and we constantly say these sort of words, you know. So—.

JAY: Yeah, this word’s completely unknown in English. Particularly when we’re talking about politics and economics, we wouldn’t consider saying something like that. So if we look at the title of your book, this massive transfer of wealth in this period of neoliberalism leads to crash, it leads to the subprime crash, it leads to the great contraction. So why does this neoliberal period lead to the crash?

DUMÉNIL: I think there are two types of factors. One type of factor is more financialization, the development of financial mechanisms to the limit. It is some kind of explosion, actually. [inaudible] and it’s related to globalization, because global—a very important aspect of globalization is financial globalization, okay, because you cannot completely separate financial and nonfinancial mechanisms, you know, because one important aspect of globalization was globalization of financial mechanisms. So this is one [inaudible] But there is another [inaudible] extremely important, which are the disequilibria of the US economy. The disequilibrium of the US economy [inaudible] deficit of trade of the US economy, which is related to globalization, the fact that the US economy is importing and buying from the rest of the world much more than they’re selling to the rest of the world. And this is related to growth of the debt of households in the country. It is related now to the debt of the government. So in the US economy, okay, a very important factor of the present crisis was the explosion of consumption, but not the consumption of everybody, the consumption, you know, of the top percentage points, you know, in the income pyramid.

JAY: Well, in the next segment of our interview, let’s talk about what working people and ordinary people should be demanding from their politicians as a solution to all of this. Please join us for the next segment of our interview with Gérard Duménil.