Welcome back to TRNN’s Climate Crisis News Roundup. In recent weeks, this column has focused heavily on the intersection between COVID-19 and the climate crisis, and that will continue as the pandemic sweeps through the world. But climate change and the politics of surrounding this important issue are still happening outside of the context of COVID-19, and we will use this space to tell those stories, too.

If you have a story you think deserves a spot in the roundup or story pitches in general, get in touch with me at steve@therealnews.com or on Twitter at @SteveAHorn. You can read the previous edition here.

False Techtopianism

A new study published in the journal Nature Climate Change has concluded that the decades of United Nations climate summit negotiations and internationally agreed targets agreed upon, have had a key fatal flaw: being based upon technologies not yet proven at scale, all of which never actually scaled up over time.

Titled “The co-evolution of technological promises, modelling, policies and climate change targets,” the study was published on April 20 by Lancaster University professors Duncan McLaren and Nils Markusson.

The researchers break up the history of UN summit climate target creation into five different eras, all of which emphasized different techtopian sales pitches offered by dignitaries in striking the international climate agreements. The effect: The climate crisis has worsened over time and international accords have been agreed upon based on false premises.

“For forty years, climate action has been delayed by technological promises. Contemporary promises are equally dangerous,” the authors said in a press release. “Our work exposes how such promises have raised expectations of more effective policy options becoming available in the future, and thereby enabled a continued politics of prevarication and inadequate action.”

The study points to technologies promised during the first climate summit in Rio De Janeiro to bring down global greenhouse gas emissions, including technology that would enhance energy efficiency, growth and preservation of carbon sinks, and expand nuclear power. All except carbon sinks have proven questionable as climate solutions, while the expansion of available carbon sinks has not actually happened.

Fast forward to today, and global temperature agreements still depend on the materialization, one day, of commercial-scale negative emissions technology. In some places, such as California, the goal is to reach “net zero” emissions by 2050. Climate policy elites concede that achieving this will require, short of radical and fairly immediate action on climate change, geoengineering. Geoengineering is a controversial attempt to reverse engineer the climate crisis recently covered here in an investigation at The Real News.

Yet McLaren and Markusson ultimately argue for an entirely new paradigm for taking climate action.

“Putting our hopes in yet more new technologies is unwise,” they said in the press release. “Instead, cultural, social and political transformation is essential to enable widespread deployment of both behavioural and technological responses to climate change.”

Their paper came just a couple weeks before the release of a May 4 study concluding that in the next 50 years, 3.5 billion people live in environments that could, in a worst case scenario, become uninhabitable from scalding hot annual average temperatures of more than 84°F. Today, only a handful of humans in desert regions experience this type of climate. In effect, this means climate refugees could become more of a stark reality in the decades ahead.

Tariffs Climate Accounting

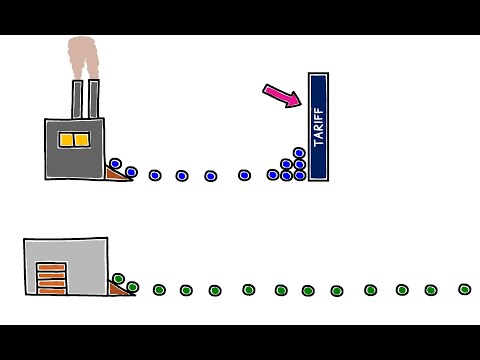

In another study about international politics, University of California Berkeley economist Joseph Shapiro concludes that the international trade system has myriad hidden subsidies for fossil fuels that do not exist for cleaner forms of energy. Thus, the international tariff system worsens the climate crisis, Shapiro surmises.

Titled “The Environmental Bias of Trade Policy,” the May 4 paper says that the “global implicit subsidy to CO2 emissions totals several hundred billion dollars annually.”

“It’s rare to find a systematic pattern that happens in many countries with broadly similar magnitude, but that’s what happens here,” said Shapiro in a press release. “This suggests that when countries go negotiate their trade policies, there is scope for that to have important large effects on the environment.”

The paper calls for international deals and tariffs to incorporate “carbon intensity” of products into the price of the goods sold on the market. That would be a way, he argues, of undoing the current bias in the other direction and to create a “carbon tariff,” or what some call a “carbon tax” when applied domestically. Legislation proposed by California Senator Ben Allen has attempted to achieve similar aims in legislation about retail products sold in the state, though the Assembly Committee on Revenue and Taxation voted it down 5-1 during the 2019 legislative session.

econimate, which produces animated videos breaking down complex economic issues into simple terms, has created a video about Shapiro’s study. Given the study is rife with economic models and jargon, the video helps cut through the noise and explains the implications of Shapiro’s findings.

Abandoned Fracking Wells

History is repeating itself with fracking in the United States both as it relates to the boom-bust economic cycle and now the prospect of thousands upon thousands of abandoned wells dotting the country’s landscape.

In previous generations of conventional oil and gas drilling in the U.S.,once a field was tapped out or not profitable, companies were left with the physical wells that no longer produced oil.Those wells were expensive to disassemble, so for companies that went totally bust, that meant abandoning the wells as “orphans.” In turn, clean up fell to the state and federal government to solve. Upwards of 3 million such wells exist today in the U.S. and they still have negative health, emissions, and groundwater impacts in communities nationwide.

Today, the issue of “orphan wells” will likely arise again soon, with many companies likely to shutter their fracking operations as the global price of oil sinks to rock bottom. Given fracking sites are industrial wastelands, with a toxic stew of chemicals injected into shale basins to extract the gas trapped in shale rock, some are already calling for the federal government to act and ensure the cleanup happens in a just and timely manner. One of those calls comes in an April 29 policy brief written by the Center for American Progress titled, “How Congress Can Help Energy States Weather the Oil Bust During the Coronavirus Pandemic.”

“The oil bust will saddle state, tribal, and federal governments with a growing number of abandoned oil and gas wells without a solvent owner to clean up the mess,” they write in the brief. “Hundreds of thousands of these orphan wells are already scattered throughout the country—a dangerous, toxic legacy of prior market crashes and inadequate bonding policies that leaves taxpayers holding the bag for cleanup costs. Decaying wells leak methane gas, contaminate groundwater, and are safety hazards for wildlife and communities alike.”

CAP has called for the creation of a $2 billion orphan well cleanup fund as part of the stimulus, which they say could create 14,000-24,000 jobs. The Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission (IOGCC), a federally sanctioned interstate compact of the 31 oil and gas producing states—which functions more like a lobbying organ—has also requested stimulus package dollars for hiring laid off oil and gas industry workers to plug orphaned wells.

Argentina’s Dead Cow

In the only commercially viable shale basin in the world outside of the United States, Argentina’s Vaca Muerta (Spanish for “Dead Cow”) Shale, the field’s production has died down to almost zero. Like in the U.S., the shale oil and gas industry there was already having a hard time staying economically viable before the COVID-19 pandemic began.

But COVID-19 has brought the industry to its knees in Argentina.

“The reality is that Vaca Muerta is not viable today and so it should be urgently re-evaluated as an energy project in Argentina,” Jorge Lapeña, former Argentine energy minister, wrote in a Spanish language op-ed on April 20.

Argentina had banked its financial future on fracking the dead cow and selling the oil and gas on the exports market. In 2018, the International Monetary Fund gave the country the biggest loan in its history at $57 billion, which is now an increasingly large debt obligation owed by the country. And fracking may not be there for the rescue, journalist Nick Cunningham—who recently reported on the Argentine fracking boom here at The Real News—explained in a recent piece published by the North American Congress on Latin America.

“The fate of the Vaca Muerta will take a back seat in the coming weeks as the debt negotiations reach a climax and the government scrambles to shield the public from overlapping debt, public health, and economic crises,” wrote Cunningham. “But the multi-year failed bet on fracking should not be forgotten. When reviewing its bailout program in 2018, the IMF concluded that Argentina’s debt appeared sustainable—a conclusion at least partially based on the assumption that oil and gas exports would increase.”

The Buenos Aires Times reported that to stay economically afloat, the Vaca Muerta would need $20 billion in investments per year. With that unlikely to happen, Lapeña put it bluntly, calling the Vaca Muerta “dead in the water” economically.

That’s it for this week. Be safe out there, and if you can, under almost all circumstances, stay at home. Thank you for reading and please come back next week for another edition of the Climate Crisis News Roundup.