Lumumba and Monifa Bandele talk about the history of Black August, continuing the legacy of freedom fighters and the Black August Hip Hop project.

Story Transcript

This is a rush transcript and may contain errors. It will be updated.

Eddie Conway: Welcome to this episode of Rattling the Bars. I’m Eddie Conway coming to you from Baltimore. Recently, we were forced to revisit Soledad Prison in California, where over 200 black prisoners taken into a mess hall, handcuffed, forced to sit back to back, shoulder to shoulder with no masks by white and Latinx guards. No black guards participated in this raid. And of course, it was just before the beginning of Black August, and it made us think about Black August itself and the role that Soledad played in that and also about the conditions now 50 some years later. So we wanted to look at Black August what it means to black people, our history and so on. And so joining me today is Lumumba and Monifa Bandele. Lumumba, Monifa, thanks for joining me.

Monifa Bandele: Thank you.

Lumumba Bandele: Thanks for having us.

Eddie Conway: Okay. So I’m going to start off with, what is Black August. I mean, we know about black history month. We know about a lot of different things. What’s Black August?

Monifa Bandele: Yeah. Thanks for asking that question because I think with the popularity of Black August, some people can think it’s just another black history month, but it’s not. It’s a very specific commemoration honoring and continuing the legacy of our freedom fighters. Many of which who found themselves incarcerated because of their activism, were killed by the state or otherwise led militant rebellions for black liberation. And so Black August was actually born in August of 1971 in the wake of the assassination of George Jackson. And he was someone who fought for the human rights of prisoners throughout the prison system and also black people in general. And so that’s the name that we’re finding too often gets lost. And so what happened is that the brothers and sisters who were impacted by his work celebrated his life every August by studying, sacrificing, doing work with each other to improve one another’s lives and found out about all of the other many historic events that had happened in August, the Haitian revolution, the various city rebellions, the birth of Marcus Garvey and created a month long celebration in the tradition of the work of George Jackson, but also encompassing so much of our very militant freedom fighting that had happened over the history.

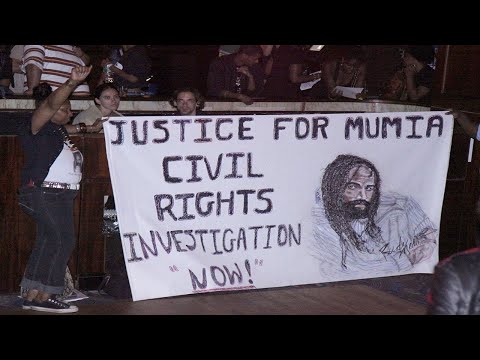

And so it left the prisons and came out into the community through many of the powerful activists in Oakland who began to have community Black August commemorations, where people fasted throughout the day and studied and worked out and read and dedicated themselves, recommitted themselves to carrying on the work of the freedom fighters that we are celebrating. And finally, I want to say, especially today, one of the key components of Black August is to fight for the freedom of our political prisoners and within that, decarcerating and abolishing prisons as a whole. So Black August is more than just another black history month. It really oftentimes celebrates those that we have forgotten or that our history books don’t want us to learn about because of the militant stance they took.

Eddie Conway: Okay, I’m going to stick with you for another minute, because I want to do a follow-up. One of the things that a criticism that I had of a Michelle Alexander’s book, The New Jim Crow, was that it did the history of the black community up to the civil rights era and then it leaped into crack cocaine. And somewhere in the middle of that, the whole black liberation struggle was missing. And one of the things that I find that writers, especially black writers, the white writers, Betty Petty bourgeoisie writers, et cetera, tend to leave out the struggle of black people historically and I’m concerned. And I wonder why that is, why there’s no talk about the struggle, the rebellion, the sacrifices our warriors made on the continent, on the ships, during slavery and up until today. Why do you think it’s ignored, the warriors, men and women, of the African people?

Monifa Bandele: Yeah. Well, I have two answers to that. One is that those of us that come out of that tradition need to tell that story. We need to create more books, more films, more cultural representations of the struggles that we come out of. I love the book by Dr. Akinyele Umoja, We Will Shoot Back. There’s not just one book on this stuff. We need to create a plethora of study and texts that highlight what happened in Haiti, what happened on the various plantations that forced the civil war to happen. It was the abolitionists doing work. We always say there’s an outside game and there’s an inside game. And we learned about the inside game, the lobbying and the letter writing and the stories and the shift in the political narrative. But there was also a very fierce rebellion growing on plantations all over the country to where the system could not be contained.

There was a push happening, not just the Nat Turner Rebellion, but many pushing us into the civil war. So that’s one thing that we have to tell that, we have to tell that, we have to document that. We hope that we’re doing that better through Black August. And then the second piece I think is really clear. We saw it highlighted at the funeral of John Lewis, where a former President of the United States took the opportunity in celebrating a leader in the civil rights movement to take a jab at a leader in the black liberation movement.

Bill Clinton: He showed us a young man. There are some things that you cannot do to hang on to a position, because if you do them, you won’t be who you are anymore. And I say there were two or three years there where the movement went a little bit too far towards Stokely, but in the end, John Lewis prevailed.

Monifa Bandele: So in describing what he thought was so great about John Lewis’ life, he said, and he was the victor over Kwame Ture. So again, there’s the mainstream narrative and there’s the white, really white supremacy infrastructure that wants to say, this is how we want you to dismantle white supremacy. This is the way we feel comfortable with your approach to dismantling white supremacy. And we have to push back and say, no, we’ve always had many tracks to our liberation. They’re all important. The work that John Lewis did was important and the work that Kwame Ture did was powerful and important, and you cannot discredit one over the other. And so I think that’s why we see more one than the other is because the state prefers our stance to be a certain way, to be non militant. I don’t say nonviolent because there was a lot of violence in the work that John Lewis and his comrades did. They were just on the receiving end of it. It was really was no nonviolent struggles, but as far as our tactics to advance our liberation, there is a curating of it, an erasure of some of the work that we did and Black August, as this tradition grows, as a way for us to say no by any means necessary.

Eddie Conway: Okay, good, good, good. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Jonathan Jackson, August 7th, 1970, and the attempt to free to Soledad brothers. But Lumumba, you, both of you all are really founding members of the Black August hip hop stuff. What is that? Talk a little bit about that movement with black artists, hip hop artists and so on.

Lumumba Bandele: Thank you. So it’s a good transition from your previous question because Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, along with Stress Magazine and at the time, a brother named Kofi Taha from Students with Jericho were charged by two of the sisters in exile, all attending the World Youth Festival in Havana, Cuba in 1997. And she talked to us both individually. They talked us both individually and also collectively saying that we need to figure out how to use our resources, our networks, our platforms, to contribute more to the freedom of political prisoners. And I want to make a distinction because the charge really was to create a program. When we came back and decided that we were going to do a hip hop program, we then decided to call it Black August. So it is a distinction and that we weren’t charged to do a Black August event. We were charged to do an event around political prisoners, and we thought that the vehicle of Black August is a perfect container for it.

And so Black August hip hop project was designed to do just that, to create a space where we could use hip hop as a tool to talk about our liberation struggle, our freedom struggle, to honor and give voice and narrative to those men, women, and other nameless folks who participated and sacrificed in our liberation struggle. We decided to do a concert in New York City and have all of the artists donate their time. And we would sort of put a twist on the traditional hip hop show. The traditional hip hop show, when you go in, you’re inundated with all of this commodification and around soft drinks, beer, cigarettes, always ever things. And so we took a twist on that and when you went into the Black August show, you were inundated around images of freedom fighters. Instead of merchandise around the room, you actually had tables being staffed by organizations who were trying to share their campaigns and people were directed to join organizations.

So it really was rooted in not only a message, but an aesthetic of black liberation and the objective was to share that information, but also direct people to become involved, and so raise awareness and raise money. And then it was an additional component, which was an international component to create a national network between hip hop communities in the diaspora and on the continent and in the United States. And we did that when we traveled internationally. The first three years, we went to Cuba, we then went to Brazil, we went to South Africa, we went to Venezuela. We went to Haiti, Tanzania, all of these places where hip hop lives. And we have some success stories. The second trip to Cuba, Common, the rap artist out of Chicago was able to go and had an opportunity to sit down with Assata Shaku and came back and recorded Song for Assata.

Now, this is important because prior to that, MXGM was a part of the Hands Off Assata coalition. And our work in that space really was limited to doing poetry readings, doing speak outs. And we had these tri-fold kind of brochures that talked about who she was. And we could probably tell that we were not getting as many people involved or informed as we should, but by taking Common and by having him have access to her, by him being able to come back and create that song, there’s no way now for us to quantify how many people know her story, how many people now are directed to her autobiography. How many people now know the real truth about her? How many people have begun to dismantle this label that the state puts on her as a terrorist. And so those are some of the main things that the concert was able to do.

Eddie Conway: Okay. And it should be noted too, that the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement has been working endlessly, tirelessly for the freedom of black people, as well as political prisoners. And that’s my question. This new movement is actually creating political prisoners, will create political prisoners and people all across the country, not only going to jail, even though it doesn’t seem like a lot is going on, it also is that a lot of people in these movements are now being killed at peaceful protests, rallies, demonstration. They’re being ran down by cars or shot, or just made to disappear. Considering that, talk a little bit about your work around political prisoners and also about what the movement activists need to be doing today to ensure that 50 years later, they’re not struggling to liberate their political prisoners.

Lumumba Bandele: Yeah. So that’s part of why we talk about political prisoners in the way that we did. And why we use Black August as that vehicle, because it’s not those individuals who were identified because of who they were, you were not identified because you’re just Eddie Conway. Shaku who was not identified because he’s Shaku, because these are people who took very radical, uncompromising stances for our freedom and the concepts still exist. This generation now has born a number of, and countless, in fact, people who may not necessarily have the organizational vehicle at the moment, but have the desire to make sure that we obtain freedom by any means necessary. That’s a dangerous position to be in because the state has shown us that they will push back on that, they will criminalize our movement. They will attempt to incarcerate our movement and they will continue to murder freedom fighters as they see fit.

And so when we talk about the history of a freedom struggle, it helps highlight the stories. It helps highlight the realities of it, but more importantly, it helps highlight the trajectory of it because it didn’t start with us. It didn’t start with you all. It didn’t start with the generation before you were part of a long trajectory of Africans, who’ve been fighting for freedom since the Europeans touched the shores of West Africa. This movement has not stopped. Our freedom struggle has not stopped. It takes different iterations, different forms and we are part of this long trajectory that will continue to grow. And so we want to make sure people know the history. We want to make sure people understand the ramifications of engaging in a certain level of struggle. And we want to make sure that people have the support necessary when they engage, how they choose to engage.

Eddie Conway: Okay. With that as the final note, thanks both of you for joining me and continue to do the work that you’re doing. It’s great. I follow what you’re doing and we need to do more of it across the board. Thank you.

Lumumba Bandele: Well, but before you go, we want to say thank you because you have been a source of inspiration for so many. And so, your freedom, your liberation, your being able to be freed from prison inspired so many of us. And for those of us who were told that the work around political prisoners was an impossible task. You are living example of making it possible. And so we thank you.

Monifa Bandele: Yeah. And I want to echo that. I want to say that currently the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, as a part of a 100 member coalition called the Movement for Black Lives. And it’s a level of organizing we’ve never seen in our lifetime. And so it is clear in every aspect of that work, the important foundation that was laid by you and your comrades, both during the sixties and seventies, but also throughout those campaigns to keep the work going while you were behind the bars, and to free political prisoners. It is evident in everything that we do, so much thanks and much honor.

Eddie Conway: All right. And thank you. Okay. On that note, we will end this and thank you for joining this episode of Rattling the Bars.

Studio: Cameron Granadino Production: Ericka Blount Post-Production: Cameron Granadino