Anthony Monteiro Part 2 – On the 145th anniversary of the birth of W.E.B. Du Bois HIS NAME looks at Du Bois’s view on racism, capitalism and the role of black workers

Story Transcript

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore.

We’re continuing our discussion about the life of W. E. B. Du Bois. On February 23, it’ll be the 145th anniversary of his birth.

And joining us again is Anthony Monteiro. He’s a professor of African-American studies at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Thanks for joining us again, Anthony.

ANTHONY MONTEIRO, PROF. AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES, TEMPLE UNIVERSITY: Thank you, Paul.

JAY: So we’ll just kind of pick up where we left off. If you haven’t watched part one of this, you probably should, ’cause we’re just going to keep going.

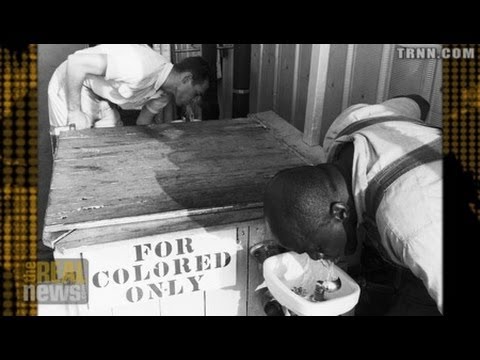

So if you look at the arc of Du Bois’s life, very early on I think he talks about himself as being a socialist. At various points he says that the question of racism is really a problem of capitalism. But that also gets mixed in different ways and expresses itself in different ways over its life. So talk a bit about that.

MONTEIRO: Yeah. That’s very important. You know, he studies in Germany and he attends meetings of the Social Democratic Party. He takes a course with the great German sociologist Max Weber, who was identified and identified himself as a socialist.

When he comes back to the United States, he identifies with socialism, especially in the 20th century, and with Eugene Debs, although he didn’t vote for him. He criticizes the Socialist Party because he differs with it on the question of race, and this will be very, very important.

Ultimately, Du Bois rethinks race and class, and he puts them in what I would call a dialectical relationship. They are mutually determining in the framework of American capitalism.

Now, that is different from what most Marxists and what most socialists, black and white, were saying at the start of the century. Most were saying that class determines race or that race was a ideological outgrowth of capitalism’s drive to separate the working class. Du Bois argues that they are mutually determining.

This understanding will finally be crystalized in his 1935 book Black Reconstruction in America. And he begins it—the first chapter is entitled “The Black Worker”, and the second chapter is entitled “The White Worker”. So he’s already looking at the racial dynamics within the working class.

But to make a long story short, his study of the Civil War and reconstruction leads him to conclude that the overturning of slavery, of the slave system, had to do with the Emancipation Proclamation and 200,000 black primarily workers joining the Union Army. They joined the Union Army not to fight to keep the Confederacy in the Union, but they joined the Union Army in a crusade to overturn slavery. So they turn the Civil War from a regional conflict into a revolutionary war to overturn the system of chattel slavery. And thus he identifies for that period the black proletariat as the vanguard of a struggle for democracy and for socialism.

JAY: And he had some very specific experience, too, which is that while he supported the trade unions and organizing of workers, he ran up against a lot of very racist union leaders.

MONTEIRO: Well, there’s no question. And, in fact, he argues in Black Reconstruction, and other places before Black Reconstruction, that most white workers were hesitant, first of all, to be in unions with black workers (this is in the 19th century), and then, as the war, the Civil War drug on, became tired of it and did not see their interest reflected in overturning slavery. In fact, many of them felt that what with the overturning of slavery, there would be all of these workers who would now be competition for our jobs and would lower our wages.

And therefore the struggle against slavery was not organic to the class struggle and the organization of unions and the fight against capital as a whole. Du Bois says for this reason the slaves become the, so to speak, advanced forces of the proletariat struggle, which focused, as Marx understood, and had to focus upon the defeat of the system of chattel slavery.

JAY: So what do you think that shows in terms of today? Do you think the equation has changed in any way?

MONTEIRO: No, I don’t. There are variations upon it, but I think in substance that equation remains the same. You know, take even voting in presidential elections for the party that is considered the party that’s more liberal in terms of race. The majority of white working people vote against that party. They see black labor as competitors and as a threat to their privileges, what they conceive of as their privileges as white workers. So Du Bois had it right: because of this, the most advanced forces—and this often is at the level of potentiality rather than actuality (a lot depends on the circumstances), but the most advanced forces of the working class tend to be the African-American workers.

JAY: Okay. Thanks very much.

Please join us for the continuation of our discussion with Anthony Monteiro about the life of Du Bois on The Real News Network.

End

DISCLAIMER: Please note that transcripts for The Real News Network are typed from a recording of the program. TRNN cannot guarantee their complete accuracy.